Best British Symphonies: 5. Ralph Vaughan Williams

It had come as no surprise to me that in a recent Twitter poll Ralph Vaughan Williams' 5th Symphony was crowned the most popular British symphony - amongst a total of 500 symphonic works by 20th century British and Irish composers, thus consolidating Vaughan Williams' (or "RVW" as he is often abbreviated) position as a leading British symphonist of the last century. He beat into second and third place William Walton's 1st and Edward Elgar's 2nd Symphonies respectively, with his own 3rd in fourth place!

It may, or may not, be coincidental that his 3rd and 5th rank amongst my favourite RVW symphonies, too (as well as the 8th). Fact is, that all nine works he has written for this genre are each individual and differ widely in their character and musical language. They can be loosely grouped into three different epochs, of three symphonies each, and each symphony - with the exception of the 7th "Sinfonia Antartica" - conservatively comprises four traditional movements. Interestingly, there is no predominance of English folk songs in any of the works, apart from some associations in the melodic shape and modal tonality of some of the themes. One finds, however, a great deal of polyphony, yet without the music ever sounding merely academical.

Symphony No. 1 "A Sea Symphony" (1903-09*) has already been discussed elsewhere. It remains his longest and largest symphony, and the only one to involve a full chorus as well as two solo voices.

Symphony No. 2 "A London Symphony" (1913-14; revised 1918, 1934) has always been one of his most popular pieces, possibly his own favourite, not least due to its evocative atmosphere, conjuring up the sounds of the capital - which RVW loved so dearly - during day and night (3rd movement: Scherzo Nocturne), including car horns, street vendors and, of course, the chimes of Big Ben. Nevertheless, the music is rarely noisy or boisterous alone, but full of surprises, real beauty and charm.

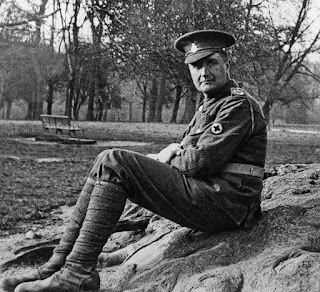

|

| Ralph Vaughan Williams in the Royal Army Medical Corps |

Staying with associations of war, Symphony No. 4 in F minor (1932-34) strikes, in stark contrast to its predecessors, with its harsh dissonances, and is often considered a foreboding of things to come. Paradoxically, it may yet be RVW's most formally conservative work, capable of standing within the tradition of Beethoven and Brahms, up to the finale's fugal Epilogue. Thus the work was well received by many contemporary composers, including William Walton and Sir Arnold Bax.

In analogy to the 3rd, the Symphony No. 5 in D major (1938-43) returns to much quieter moods, despite - or some say because - of the times of war during which it too was written. It is made up of material from his opera The Pilgrim's Progress, after John Bunyan's allegorical novel, which took RVW decades to write, and only to be completed long after the 5th Symphony. It is here also, that Vaughan Williams masterly applies the contrapuntal writing and the motivic work of his much admired Tudor style, in a way he had explored back in 1910 with his Fantasia on a Theme by Thomas Tallis. It all culminates in the Passacaglia of the final movement. But it is the overall coherence, melodic beauty and tranquil serenity which have fascinated music lovers ever since the first performance in 1943 under the composer's baton.

Symphony No. 6 in E minor (1947) may yet be considered RVW's most mature symphony: the mastering of form and sound (note the addition of a tenor saxophone, harp and an enhanced percussion section) is unrivalled, the harmonic progressions are much more modern, although being perceived as less dissonant than those of the 4th, which is due to an improved style of instrumentation. Whilst the first three movements follow a traditional pattern, it is the eerily quiet Epilogue which ends the work - pianissimo throughout - that marks possibly the most radical and most progressive part of all of RVW's symphonic output. All movements are played without a break, thus unifying the whole symphony, which requires great levels of attention from both performers and listeners alike.

The Sinfonia Antartica (Symphony No. 7; 1952) is somewhat of a novelty which owes its gestation to RVW's film score for "Scot of The Antarctic". Less a symphony than a symphonic suite, it nevertheless contains beautiful depictions of a vast icy world and its few inhabitants, swept by constant gales (the wind machine features a prominent part throughout!), with the occasional aid of a soprano solo, a female chorus and an organ. Each of the five movements were given individual quotations from various literary sources, which are often recited during a performance.

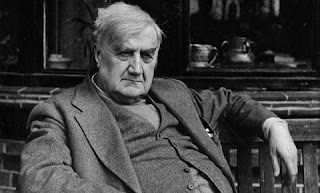

|

| RVW in his later years |

Equally unusual, albeit in a different way, is the "little" Symphony No. 8 in D minor (1956), less complicated than most of its predecessors, but filled with lovely sounds and musical playfulness. The headings of the four movements differ, too, which are titled: Fantasia (Variazioni senza tema), Scherzo alla marcia (wind instruments only), Cavatina (strings only) and Toccata. Through an abundance of exotic percussion instruments the work invokes certain reminiscences of Puccini's opera Turandot, yet it remains recognizably a masterpiece of its creator RVW, and has been cherished by many performers, not least by its dedicatee and conductor of its première, Sir John Barbirolli.

Symphony No. 9 in E minor (1956-58) dates from the final years in the composer's life. Despite its solemn tranquillity, its maturity and enlarged orchestration it has often failed to make a lasting impact on audiences. Whatever the reasons may be for this - be it the apparent lack of recognisable melodies, its often sombre tone, or the simple fact that it is outdone by some of the previous symphonies - this piece forms somewhat of an anti-climax to the series, unlike the 9th Symphonies of Beethoven, Bruckner, Dvořák or Mahler. Nevertheless, it is still a beautiful piece of music, and a fitting farewell by its composer, marking the end of a long and successful career which included some of the greatest contributions to the genre of British Symphony.

RVW's symphonic cycle has been recorded over and over again, including by Sir Adrian Boult, Sir John Barbirolli, Leonard Slatkin, André Previn, Bernard Haitink and Sir Andrew Davies, to name just a few; there have been new complete recordings by a number of talented younger conductors lately - so it is nigh impossible to pick a favourite. However, one of my personal champions of these treasured works will always be "Glorious John" (Barbirolli).

______________

* Quoted here are the year(s) of composition, rather than of first performances or publication.

Why not visit the website of the Ralph Vaughan Williams Society?

ReplyDelete