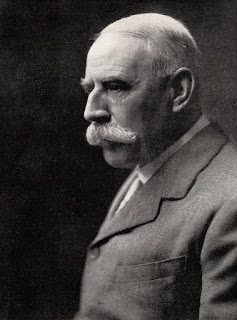

Best British Symphonies: 7. Sir Edward Elgar

Elgar's music needs no introduction: his most famous pieces feature on many concert programmes around the globe, not least during the annual 'Last Night of the Proms'. Despite his undeniable love of Edwardian pomp and circumstance, Elgar had throughout his life been a rather private person, and this reflects in much of his music. Although a friend and admirer of the German Richard Strauss, the two couldn't have been more different. The former became internationally acclaimed for his programmatic tone poems and operas, of which Elgar has written none (the programmatic references to several friends made in the Enigma Variations remain more the less vague and indistinct), whilst Strauss - unlike Elgar - produced little in the form of cantata, oratorio, traditional chamber music and symphony, all of which were Elgar's stronghold.

|

| Sir Edward Elgar |

Elgar completed two symphonies and left sketches for a third. They all follow the customary four movement blueprint and are - in line of late romantic fashion - expansive, albeit not excessive in length nor instrumentation (unlike other contemporaries, he did not follow the Beethoven/Mahlerian practice of introducing human voices). On the surface, Elgar remains as reactionary as before him Parry and Stanford, or Brahms and Bruckner, yet the real beauty of Elgar's contributions to the genre lies within the music itself.

The First Symphony in Ab major, op. 55, was written in 1907 and premiered by Hans Richter (its dedicatee) and the Hallé Orchestra in 1908. Like Brahms, Elgar was over 50 years old when composing his First, but this is to no detriment to the piece, thus showing the craftsmanship of Elgar's mature style. Much of the symphony, except the Scherzo, passes in a relatively slow or moderate tempo, with his favourite marking nobilmente characterizing the opening motto. Thematic links and connections are knitted across the movements, in more or less obvious ways (a technique he may have picked up from Brahms' Third or some of Strauss' tone poems), especially in the connected II. Scherzo / III. Adagio. Unusually in any piece of a Classical structure, some of the main sections of the outer movements and the Scherzo are touching several far remote tonal centres, but to restore unity, the Finale ends with an apotheotic return of the opening motto in the original key of Ab major.

The Second Symphony in Eb major, op. 63, followed just a few years after, during 1910/11 and was conducted the same year by Elgar himself. Here he appears to be even more confident in tackling the overall form and the musical intricacies than in his First. The result is an homogenous, exciting piece full of melody, grand sonority, masterly instrumentation, convincing thematic and harmonic relationships - and even deepest tragedy in the slow II. Larghetto, an dirge on the death of Edward VII -, a typical Elgarian masterpiece in other words! Instead of the traditional tripartite Scherzo, Elgar presents us with a fast Rondo conjuring up the sounds of some of his Pomp and Circumstance marches, after which follows a serene, gently flowing Finale. Headed by a motto by Shelley, the Second Symphony is full of literary connotations throughout, and just like in its predecessor, the opening theme / motto of the first returns at the very end of the last movement.

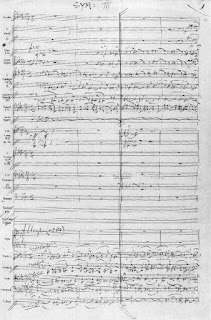

|

| Opening sketch of Elgar's Third |

Following the death of Elgar's beloved wife Alice in 1920, Elgar's musical output suddenly waned. Was it not for a possible commission by the BBC and the encouragement of his friend George Bernard Shaw, he would probably never had considered writing another symphony. Yet from the extensive sketches that survived (and were collated by his great friend Billy Reed) - the opening pages are even fully sored - we can conclude that the new piece had grown and taken shape considerably in the composer's mind. We can also conclude that this Third Symphony in C minor is much advanced in its musical and harmonic language compared to the previous two. Would it not have been for the tireless and skilful work of the late Anthony Payne (who died in April this year) - who after a long and arduous struggle (of more than two decades) with the Elgar trustees gained the permission to officially complete the symphony (secretly he had started much earlier) by collating and elaborating the surviving sketches, we would never have had a performing version of Elgar's unfinished masterpiece!* How much of the piece is Elgar, how much Payne may never be fully established, but it is beyond doubt that Payne managed to feel his way into Elgar's thinking and sound world, and we can safely conclude that Elgar would have been fairly pleased with his completed Third Symphony (therefore often listed as the "Elgar/Payne" in our modern concert repertoire).

|

| Sir Edward Elgar in later life |

There are - naturally for a composer of such renown - many fantastic recordings available, some of the earliest under the composer's own baton, made for HMV in 1927 (2nd) and 1930 (1st) respectively (remastered and available on Naxos). Every conductor of rank and with interest in English music has since contributed to the ever growing catalogue of recordings, obviously less numerous to date for the Third due to its publication not until 1998. I would be torn to pick my favourite recording, but I am fond of Barbirolli's late (1970) recording of the First and his earlier (1964) commercial EMI disc of the Second, both with the Hallé.

* It is well worth reading Payne's detailed account of the gestation of his performing version. Anthony Payne; Elgar's Third Symphony. The Story of the Reconstruction; Faber and Faber, London 1998

Comments

Post a Comment