Organ Symphony No. 1 - on Lutheran Christmas Chorales

The Lutheran Chorale in classical music

|

| Martin Luther |

Johann Sebastian Bach gave the Lutheran Chorale its firm place in music. With him it occupies two fundamental main roles: In his cantatas and oratorios as four-part homophonic choral settings, providing a 'commentary' to the story told; and, in a more embellished, individual form, as ‘Chorale Preludes’ for organ (Choralvorspiele or Orgelchoräle) to be played before the communal singing by the congregation during the Protestant service, evoking and consolidating the relevant mood expressed by the tune and by its text.

Whilst widely incorporated in the works of his predecessors and contemporaries, many great composers after Bach - mainly of Germanic origin but regardless of their faith - continued to find inspiration in the chorale or used specific ones in their works: As a fellow Protestant, Johannes Brahms used chorales in his organ and religious choral music; the staunch Bavarian and Catholic Max Reger expanded Bach's version of the Choral Fantasie to the highest expressive level known within the organ repertoire; the Jewish-born Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy used one of Luther's most famous chorales ("Ein' Feste Burg Ist Unser Gott!") in the finale of his 5th symphony, the 'Reformation'; and Richard Wagner based a whole opera on the subject of the 'Master Craft of Singing': Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg. In the 20th century, Hugo Distler, Sigfrid Karg-Elert and Ernst Pepping took the Lutheran Chorales to a new and contemporary form of expression.

Throughout history, however, the use of chorale melodies as substitutes for the contrasting themes within a classical sonata form has not previously occurred. To find out how these ancient tunes adapt to the 18th century principle of juxtaposing different subjects, developing and recapitulating them in a dramatic move from the tonic to the dominant (or the mediant or another distant tonality) and back to the tonic, it pays off to have a closer look at some of the chorales themselves. Rather than this being a general treatise on the matter, we will analyse only the chorales used in the Organ Symphony No. 1.

The Lutheran Chorales of the Organ Symphony No. 1

Four chorales make up all the musical material of this work: two for the season of Advent (nos. 1 & 4) and two for Christmas (nos. 2 & 3):

I. "Nun Komm' Der Heiden Heiland" (Martin Luther 1524, after Veni redemptor gentium by Bishop Ambrosius ca. 340 - 397)

II. "Vom Himmel Hoch Da Komm' Ich Her" (Martin Luther 1539)

III. "Es Ist Ein Ros Entsprungen" (15. century, by Michael Praetorius 1609)

IV. "Es Kommt Ein Schiff Geladen" (Anon. Cologne 1608)

Harmonically the chorales are based on either the Dorian (nos. I & IV) or the Ionian (nos. II & III) mode. The unifying principle, however, is found in the melodic progressions of the opening phrase of each of the tunes: tone repetitions, stepwise movements in major/minor seconds and leaps of thirds or fourths.

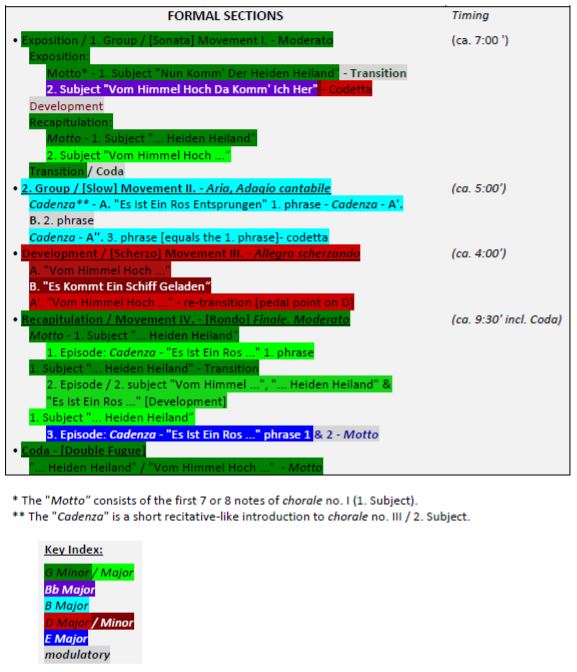

The strict rules of 16th century counterpoint apply to all the chorales regardless, which makes them ideal to all sorts of contrapuntal elaboration, as shown throughout the whole of the Organ Symphony No. 1 and culminating in the double fugue of the final coda. To illustrate how these are combined to take up their individual roles within the building plan of the classical sonata movement, the following diagram provides a better understanding:

Considerations of Form and Cohesion

As exemplarily demonstrated by Charles Rosen, the sonata form comprises the creation of drama through the modulation from the tonic to the dominant / mediant during the exposition; a subsequent development of the musical material; and a consolidation of the tonic during the recapitulation and coda, therefore roughly creating three equal sections. However, the sonata / symphonic form at its height in the outgoing 18th century usually sported four movements (Allegro - Adagio or Andante - Minuet/Scherzo - Finale: Allegro or Presto). Arnold Schoenberg's attempt - little over a hundred years later - to combine both the sonata movement with the four movement framework (in his String Quartet No. 1, op. 7 & Chamber Symphony No. 1, op. 9) yielded some satisfactory, yet by no means fully satisfying outcomes, and he soon after abandoned the idea completely.

As it can be seen from the timings indicated in the table above, the 1. & 2. subject groups take up nearly half of the overall performance time of the Organ Symphony No. 1, therefore shifting its balance towards the exposition (or rather two expositions, one also appearing as part of the 1. group) and - at a first glance - lessening the importance of both any in-depth thematic elaboration during the main development section (i.e. III. Movement / Scherzo), and a thorough affirmation of the tonic within the recapitulation - which has now become a busy rondo form with alternating episodes and an additional development (the 3rd overall). Whilst the introduction of an additional theme during the development is nothing new or unusual (see Beethoven’s "Eroica"), and here provides little else other than a trio episode within the scherzo, at least there are nearly ten minutes of music in the minor and major tonic during the recapitulation and coda, restoring somewhat the overall balance which had been so important to the Classical masters.

Whether for an equilibrium of the formal scheme it would be advantageous to place the scherzo movement as the 2. group and develop all thematic material during the slow movement - as shown in the author's String Quartet No. 2 "Choros" - or to use the present model of a slow 2. group and a scherzo-development, shall possibly be decided in future projects of this nature. The listener meanwhile may make up his or her mind based on the examples provided thus far by the aforementioned works. It certainly will not be an easy decision, and should involve the repeated listening to those works, just as recommended by Schoenberg with regards to any serious piece of contemporary music.

Comments

Post a Comment