Best British Symphonies: 8. "Celtic" Symphonies

Sir Granville Bantock ("Hebridean" & "Celtic" Symphonies), Sir Arnold Bax (Symphonies 1 - 7) & E.J. Moeran (Symphony in G minor)

Granville Bantock was a good friend of the composer Joseph Holbrooke, and both not only shared their love of Celtic Britain (the Hebrides in the former's case, Wales in the latter's), but also established a similar musical style, at times strongly influenced by Wagner. Although Holbrooke did not write any symphonies with a specific Celtic theme, he often used evocative titles for other pieces and, for example, named his First Piano Concerto The Song of Gwyn ap Nudd, telling the story of an old Welsh legend. He also composed a cycle of Welsh folk-tale operas called The Cauldron of Annwn. Both men visited each other a great deal within their two favourite countries - Bantock also occupying a number of holiday homes in Wales - and subsequently drew inspiration from one another.

Surely, each of these composers deserves his own blog post. But there is at least one common aspect which unites these three great 20th century symphonists, allowing their works to be discussed together here: the influence of both the landscape and culture of the original inhabitants of the British Isles, its Celtic peoples. There are other contemporary composers, too, who display a similar interest in ancient Britain, however, neither John Ireland nor Peter Warlock, for instance, have written any symphonies, and others have already been discussed in a previous post.

Born in London of Scottish descendance, Sir Granville Bantock's (1868-1946) works show many influences of Celtic, ancient Greek and Oriental origins, not least in his symphonies: his first (and largest), thus entitled "Hebridean Symphony", was completed in 1915 and premiered under the composer in 1916. The Hebrides - and in particular the folksongs of these islands - made a profound impression on Bantock, which in this symphony shines through the music during the different sections of a continuous single movement, depicting various scenes of Highland and Island life and its associated natural backdrops. The musical moods change throughout, from beautifully romantic, atmospheric, at times rhapsodic, to almost tempestuous and triumphant, before the piece at last finishes on a "jazzy" chord.1 A poetic programme runs throughout this symphony, therefore being more akin to Bantock's shorter orchestral pieces and Poems with Scottish or Celtic subtitles, rather than to the more traditional specimen of the symphonic genre which we can find - most notably - in the outputs of Stanford, Parry and Elgar.

|

| Isle Of Skye - watercolour by James Orrock |

A bit more of an oddity is Bantock's "Celtic Symphony" from 1940, scored for strings - divided in up to seven parts - and six (!) harps. In this work, too, the composer incorporates his beloved Hebridean folksongs, and the work is presented once again as a single movement divided into the different sections of a traditional symphony. The sound created by only stringed instruments is unusual, wistful and archaic at times, where calm, tranquil scenes are intersected by folk-dance like episodes. The modal tonality of the folk tunes and their Lombard rhythms are more prominent here than in the "Hebridean" and being intensified even more by the sound of the harps (which here are treated predominantly as the archetypical Celtic instrument).

|

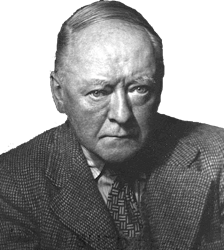

| Sir Granville Bantock |

***

By quantity, Sir Arnold Bax's (1883-1953) symphonic output comes a joint third with Sir Charles Villiers Stanford's and Sir Hubert Parry's (with seven symphonies each), to be surpassed only by Ralph Vaughan Williams' nine and Havergal Brian's thirty-two; just a few later 20th century-born British composers (e.g. Edmund Rubbra, George Lloyd, Richard Arnell, Robert Simpson, Malcolm Arnold, Arthur Butterworth and Peter Maxwell Davies) would write symphonies at this rate again.

Bax was born in London, the same as Bantock and Moeran, and, likewise, soon fell under the spell of the Celtic countryside, namely the West coast of Ireland where he spent long periods of time at a number of - often secluded - locations. To discuss his symphonies thoroughly would require a separate blog post, and has been done in much detail by a number of people, no better so than in the recorded interview with the late Vernon Handley, one of Bax's music best conductors.2 The symphonies can be loosely split, not dissimilar to those of Sibelius, into three groups, with, in my point of view, nos. 1-3 (written between 1921-29), nos. 4-6 (1930-35) and stand-alone no. 7 (1938/39) marking the different periods of their composition as well as some slight stylistic variations between them. Other writers have grouped them as nos. 1-3, stand-alone 4 and 5-7, although opinions do differ on this matter.3

The unifying factor of all seven is, without doubt, that they are composed in three (not four or more) movements, roughly as fast - slow - fast; however, in most cases the fast movements start with a slow introduction and - with the exception only of the First and Fourth - fade away in a slow ending or epilogue after the third movement, thus creating the impression of a number of varying episodes, despite the overall clear formal construction and thematic interconnections. A further commonplace is the sheer brilliance in melodic and harmonic invention and the pallet of orchestral colours, which make these symphonies unmistakeably "Baxian", despite many influences of Wagner and Sibelius, and an often powerful rhythmical drive reminiscent of Respighi's symphonic poems or even the later film scores of Miklós Rósza. Yet each symphony has its own individual appeal, and it belongs to one's personal taste and preference to decide which of the seven symphonies would be crowned the favourite: the Third may have become the most popular in concert repertoire, but the Sixth has the ability to evoke the most profound feeling of depth and mysteriousness whilst the Fourth appears the most powerful and dynamic.

Although not much of the composing of the symphonies did actually take place in Ireland (the Third and Seventh were mainly completed in Scotland, and many of its predecessors in London and Southern England), the spirit, the solitude and the natural beauty of Celtic Ireland - in its Western counties of Kerry, Galway with Connemara and Donegal before all others - permeate these masterpieces throughout. Without Ireland, Arnold Bax as we know him today, and whose alter-ego was the Irish poet Dermot O'Byrne, would be unthinkable, and neither would he likely have written seven magnificent symphonies without Eire's ancient culture and landscape being constantly present in his mind and imagination.

***

Ernest John Moeran (1894-1950, who was called Jack by his friends) spent most of his early years in Norfolk where he fell deeply in love with the landscape, its people and their folk music - also with the way Ralph Vaughan Williams had incorporated the county's folk songs in his "Norfolk Rhapsodies" and "In the Fen Country", hence inspiring the young Moeran to follow suit and to base much of his own music on folk song idioms.

|

| E.J. Moeran |

His only finished Symphony in G minor4 took many years to complete, with an earlier version from 1924-26 being commissioned by the Hallé Orchestra but then withdrawn, and the second, final version being completed almost a decade later from 1934-37, following various revisions in between. By that time, after having moved from place to place, Moeran spent most of his time in Ireland, particularly in Kenmare in County Kerry, the very town where later in 1950 he died under somewhat mysterious circumstances.5

Despite clear influences in the symphony by many of his contemporaries - first and foremost to be noted are the Sibelian soundscape of the second movement and the Nordic folk dance rhythms of the third - it is the direct inspiration Moeran drew from both the Norfolk fenlands and the desolate Irish mountains and coastlines that characterize this symphony. The work may appear traditional in its formal conception, with a classic four movement structure and sonata form firmly in place, but there is something special and almost metaphysical about this symphony which may only be explained as stretching towards the inmost of Moeran's very nature: melancholy and wistful at times, it is nevertheless a strongly determined work, deeply rooted in British folk music and a tribute to both its landscape and its people.

|

| E.J. Moeran's grave in Kenmare churchyard |

The unusual aura about Moeran's Symphony in G minor has lead to much criticism at first, but fortunately, this, his only finished contribution to the genre, has nowadays become a better appreciated and more frequently performed, as well as recorded, addition to the repertoire of great British symphonies.

***

There are today a good number of commercial recordings available of all the symphonies discussed in this post, yet, sadly, most of them are rarely performed in our concert halls. To pick a favourite interpretation is down to one's personal choice, but for me Vernon Handley and Bryden Thomson for their complete Bax cycles stand out (plus Handley's Bantock and Moeran symphonies), despite there being several more excellent readings of most of these works, including the ones by Adrian Boult, John Barbirolli or David Lloyd-Jones.

-------

1 with an added major 6th in 1st clarinet & major 7th in a muted 1st trumpet

2 The interview is available through the Chandos Box Set both recorded and as a transcription in the booklet.

4 A second symphony, in E♭ major, has only survived as sketches, although these have been masterly completed in 2011 by the conductor Martin Yates. This work would have differed much from its predecessor by being a more optimistic, even positive work and formally more compact, with the movements elaborately transitioning from one into the other.

5 Moeran died possibly of a haemorrhage due to his lifelong excessive alcohol consumption, when he fell off the end of Kenmare's pier.

Comments

Post a Comment